Greece: Thoughts on Stillness

Between the stresses of family business, being a job-hunting youth, and otherwise struggling with daily meaning since finishing education (for now!), this retrospective was a long time coming. While it won’t be the last time I talk about this trip, going forward I’ll be focusing more on book reviews and personal essays. Thank you for your patience as I find my way, and I hope you enjoy!

As all travels do, the time make my odyssey to Ithaca snuck up faster than I anticipated. Well, not actually Ithaca, but if you look at a map, Kefalonia is, as the scholars say, spitting distance. It was time to embark on my journey, with it came the stirrings of wonder and fear about what exactly I’d gotten myself into. No more could it be a future occurrence that rooted me in a tumultuous summer of figuring out what it means to truly be an adult (and the horrible realization that maybe no one really does?). No more could various friends and family poke fun at the possibility of meeting someone Mamma Mia style, which, while I’m glad was an entertaining idea for them, was never remotely in the cards. The future had become present and uncertain, and eventually would pass too. Soon I’d have other things to count down to.

The journey began with a 5am alarm and a slick and snowy Halloween morning. My wonderful roommate dropped me off at the airport even though it was only her second day of work at a new job. I looked at the weather forecast for Athens, cackling with glee that soon I would be in mild sunny 70 degrees, a lovely contrast to the chilly days prior spent curled around a hot water bottle for warmth since our radiators hadn’t kicked in yet. My roommate and I discussed important last details—bills, logistics for the holidays, and more. I’ll be honest I don’t remember much. I was too focused on hyping myself up to sprint through Canadian customs to catch my connecting flight with just under an hour-long layover.

Why would I need to go through Canadian customs, you ask? Fantastic question, dear reader. It’s because I wanted to be cheap, and so my aerial journey comprised a total of 3 flights: firstly, from MSP to Montreal; secondly, from Montreal to Toronto; and lastly, the long haul from Toronto to Athens. The Montreal layover, because it was connecting me to another domestic location, meant that I would technically be entering the country and so had to negotiate customs. Not a snafu to trifle with on such tight timing. But I figured that by harnessing the spirit of American Exceptionalism I could outrun the border security if I needed to—this arrogance undergirded by the fact that one time I sprinted across Newark airport, terminal A to terminal C, and caught a flight with exactly a minute to spare. And besides, it wouldn’t come to that; it would probably be fine.

I gave my roommate a hasty, but in my memory effusively grateful, goodbye, as I felt a bit sheepish for the imposition—people who do airport pick-ups or drop-offs really are the backbone of society—then trotted my way to the Air Canada counter. Even though I had already checked in, I wanted both the physical security of a paper ticket and the tangible memento of it all. After eating some overpriced breakfast, I waited at my gate underneath the garish cold overhead lights.

The three gate agents were gossiping about the treacherous weather, the nitty gritty of clocking hours and trying to get promotions, and the onerousness of fitting anti-sex trafficking training into all of it. The minutes clicked closer to boarding time while people slowly trickled to the gate and bid their time. A Japanese lady FaceTimed her family. A mennonite woman read her bible so quietly she seemed like a living statue. I looked out the windows at the tarmac below shrouded in the lavender pink of Minnesota twilight. The plane clearly was not on, and there was no sign of the flight crew.

Dead dark windows above its nose and itself immobilized, a part of me wondered how this metal corpse could ever fly. What could revive it? Just as I was certain that the plane was well and truly dead, the flight crew arrived a minute after boarding time.

Checking the clock, I was pleased that we were still making good time. But then all that time went away. You see, Minnesota gave me a real Minnesota goodbye, and the cold snap that had left me shivering in my apartment now left me grounded. Lights roved around the plane, crane necks and cherry picker heads, spitting orange mist and fog, swooped by in black and yellow shadows and were blurred by the crusted frost on the windows. De-icing the plane took an hour.

Arriving in Montreal left me with little confidence that I could make it, but I tried all the same. 10 minutes until the gates closed. I hadn’t prepared for it. I wasn’t even born for it. I was gonna try to make it anyways. I was never a fast runner, but golly can I speed walk, so that’s what I did. But carrying thirty pounds on your back and pulling another thirty pounds by your side is pretty exhausting. And the labrynthine halls waned my confidence. Airports always seemed too big inside compared to the outside. Montreal was no exception. Turn after turn after turn. Meeting an official who directs me one way. More hallways and turns and cold halogen lights, and then finally emerging into a real space with bright ceilings and natural light and people talking to each other. I’d made it to customs, which was, for the record, pretty easy to do quickly. I walked up to a kiosk, and answered the questions (how many days are you in Canada? Do you have anything to declare?). I didn’t even really have to talk to an agent—one look at my receipt and they waived me through.

Unfortunately for me, I arrived at my gate just three minutes shy of the departure time. And none of the sprinting in the world would have saved me—the flight had left early anyways. So, with my arrogant American tail between my shaking panicky legs, I humbly beseeched the gate agent for her assistance.

I truly was running all the calculus in my head about how I was going to haggle with Air Canada about how to get to Athens, preparing myself for an extended traveling snarl, viciously digging through the recesses of my mind about my hostel’s no-show policy, and more.

But then the gate agent said something that astounded me to silence. “I don’t see you on the manifest.”

Not on the manifest! What in the world did that mean? Oh gosh, I used Expedia to book these tickets, did something super rare go wrong?

“It looks like you were automatically rebooked for the next flight. It’s at the gate just next door—your final destination is Athens? I’ll reprint your boarding passes for you.”

The agent looked at me oddly, though not unkindly, as I lavished my gratitude on her, marveling at reasonable airline policy that seems fewer and far between these days.

From there, I hopscotched to Toronto and then to Athens, where I landed in midmorning to beautiful sunny weather. Mid-70s and an appropriate amount of humidity. It was beautiful. It was old. I was nearly falling asleep on my feet. Dehydrated because I had forgotten my water bottle at home. Starving.

I bought a phone charger. I got lost in the streets. I gorged myself on fresh pita and tzatziki, loukoumades slathered in pistachio praline, gyros with fries, as I strolled through the plaka and monastiraki. I tentatively pet the wild cats that begged for food. The most excitement I ever got up to was climbing up the hill to the Acropolis (the wrong way, which is to say the EVEN STEEPER way) and beating the crowds to those old ruins, where I wandered around for hours. I saw the olive tree that according to myth had been planted by Athena herself, and even while it wasn’t the purported original tree, it had been grown from its cuttings, somehow germinating itself over and over again. Given how many times the Acropolis had been sacked throughout thousands of years of history, its a marvel anything remains on that hill.

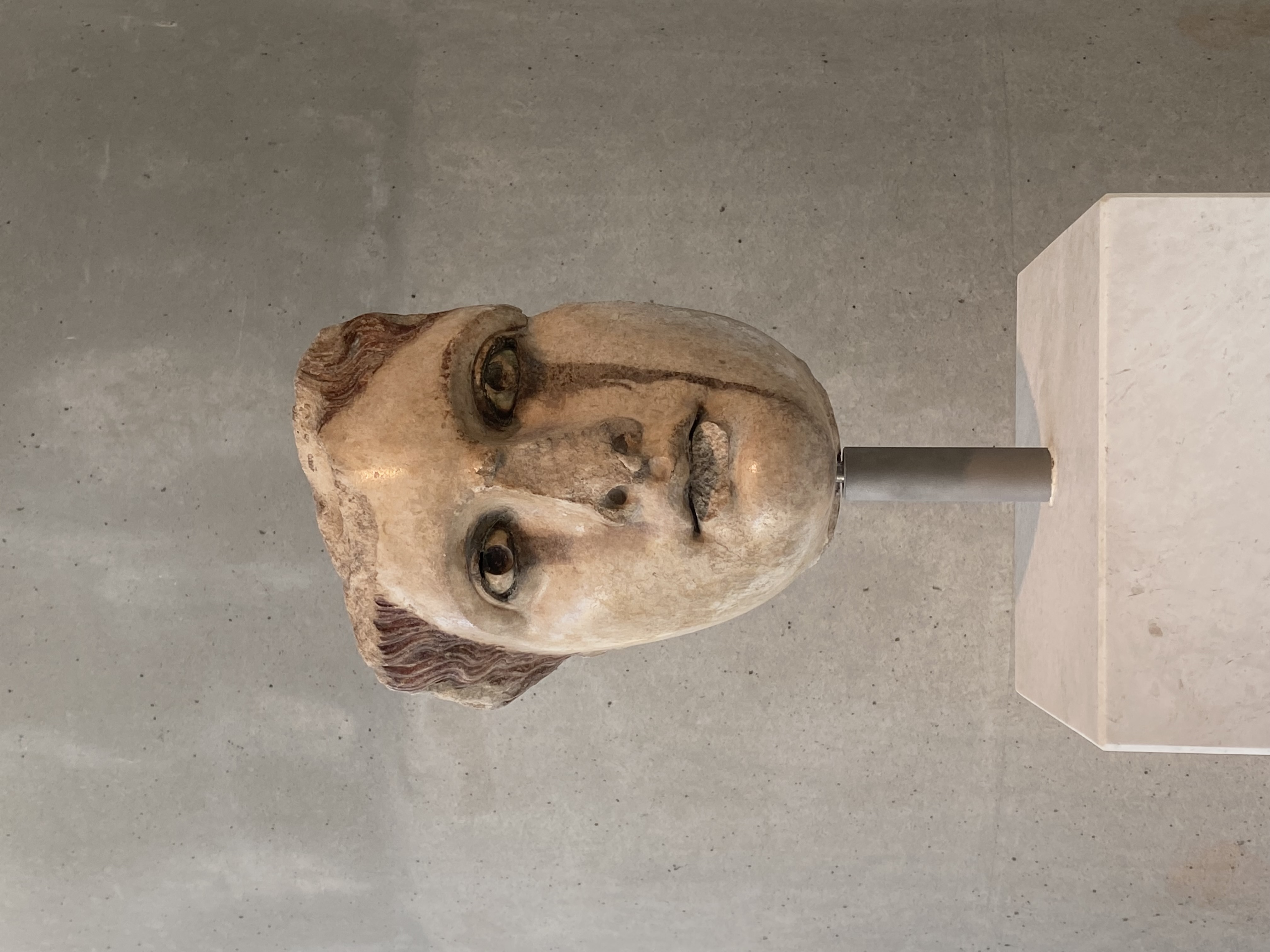

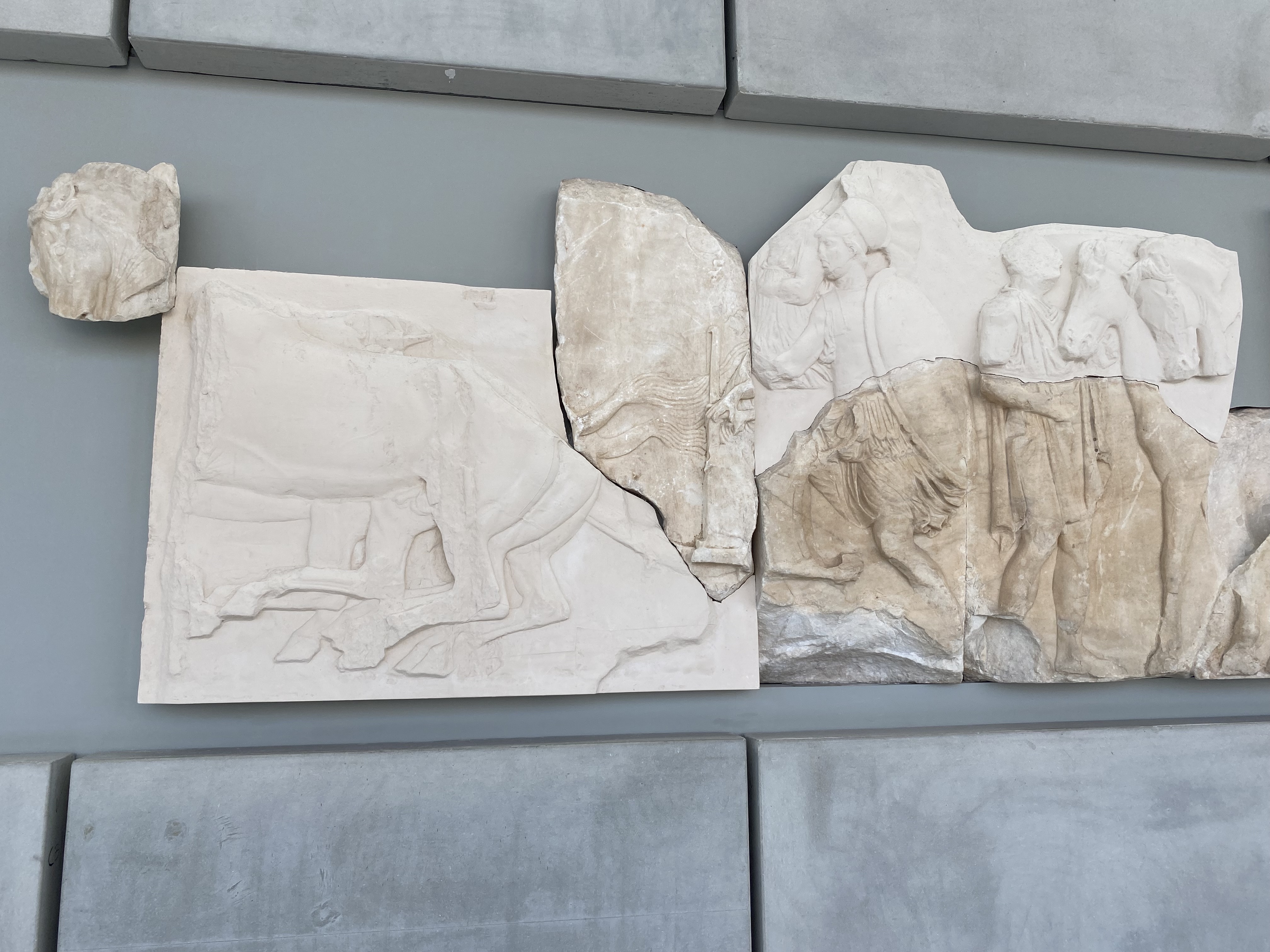

In the Acropolis Museum, the statues and artifacts, save for the most fragile few, all stood out in the open. There were traces of vibrant, almost garish powder, from when the statues were painted. Then I turned around and jumped back in fright at a tear-stained marble face. The placard read that the pigments from the eyelashes had stained its cheeks from rain and weather. The parthenon marbles were a patch worked together between recreations and the real deal, strung up high on the fourth floor arranged as they were on the Parthenon in antiquity. Alabaster casts replaced where some of the pieces ought to be, pieces that were strewn about Europe, but mostly the British Museum.

Amidst these wanderings, I missed my friends and my home something fierce and never felt more strange to myself than I had in Athens. I’d always prided myself on my independent nature, a nature that I often felt so acutely it was at times dangerous in its own psychic right. I always wanted freedom, to pick up and run and follow my whims wherever they took me. Sometimes I would simply be struck in awe, watching a painted train speed by and locals mill about their daily lives, by Athens’ banal and yet emphatic realness, how lovely it is that people are people no matter where you go, and turn as if to remark this to a friend, but of course there was no friend there. I had flown alone.

Hyper-independent introverts like myself often remark how being alone is different than being lonely. Alone is peace. Alone is intentional. Alone is fulfilling. Lonely is externally imposed, something pitying from and extroverted society at large that can’t reconcile a person who skirts its expectations of what a fulfilling life ought to be. I’m not so convinced of this anymore. Wandering around for three days in Athens, I kept on running into these moments where alone turned into lonely on my own terms. Alone looked less intentional and more like capitulation. Lonely seemed more like rebellion.

Of course this realization scared me. So instead, I took pictures of the train running by, and lamented I hadn’t organized my time better. I spent three days wandering the same neighborhoods in Athens—surely if I had planned ahead I could’ve made it to Meteora and Corinth. But I wouldn’t have made it anyways, since the railways to both of these places were under repairs from historic flooding during the summer.

One propellor plane and a taxi scam later, I had made it to the farm. The town was a forty minute walk away—I figured this out the hard way from the aforementioned taxi scam. Being in Kefalonia felt like my entire nervous system had shifted down three gears. No hustle and bustle of the city. I woke up every morning with Ithaca looming in my window. Everyday came with naughty horse troubles. I chased escapees through thorns and thickets, onto roads with blind corners and somehow none of us got hurt. I broke up fights between stallions and mares. I would eat lunch with my host who told me stories about his arsonist cousin who was in jail, and my host would beg me to eat way more olive oil when I was being too precious with it.

In my time off of volunteering, there was nothing to do, because the tourist season was over, so I, ever the person full of twists and turns, would wander through town, peruse the local grocery store from curiosity of what processed foods looked like abroad. Then I would sit on the stony shore and watch the occasional ferry slowly chug its way from Sami to Ithaca. I would journal about the strange stories my host told me, or how I got in trouble for not letting in the milk man even when I absolutely did, or how silvery the olive leaves looked at dusk.

I even managed to get myself lost outside in a hailstorm. The weather was mercurial. Sunny and mild one minute, then sleeting the next, and it tricked me. The wind blows hard in the Mediterranean, hard enough to make your ears pop. Sleet and rain lashed my face. But I found my way back, soaking wet and cold. I drank warm goat milk for dinner, which made me happy.

I was content with most of this, from the pace of life to working with the animals. Naively though, I used one lazy afternoon to apply for jobs because I felt like I ought to be responsible. I don’t even remember what the positions were or why I felt so pressed to do it. I think it was because I did not like being still or missing home or realizing with overwhelming certainty that there was no me to find in Greece that I didn’t already have within me. There was no hidden purpose to discover and covet like a relic to bring back home and cherish in my own museum for the sake of preseving the feeling of wonder indefinitely. I think all I felt was that I had left my life, and I hadn’t felt like I had a life to leave before. I think I wanted to start living my life and that, ever the American I am, the way to do that was to get a real job. Or maybe I wanted to hide.

But I don’t remember the jobs. I’m not even sure I remember the hardships of shoveling manure when I was in Kefalonia. I remember that shoveling was meditative. I remember the rotting autumn pomegranates, the seemingly endless olive groves, how the clouds obscured the horizon and how on the clearest days you could see all the way to the mainland. I remember watching the barn kittens sleep in the hay bales. I remember the soaring pine trees, and learning how to banish curses from the black cat that followed me everywhere.

I missed home. I missed my friends and family. And I didn’t know how to miss something and stay away.

The first day of December, my dad texted me to let me know that my yia yia was dying. He tried to tell me to stay for the two weeks that remained, but I quickly told him off and made arrangements to come home. I wanted to try and make it in time to say my goodbyes. It took me two days, and my yia yia died during my layover in Istanbul.

My dad picked me up from Dulles and I told him about all the walking I had done. When we made it back to my hometown of Richmond, Virginia, my mom helped me buy funeral clothing.

Three weeks after I returned, I stepped into a Greek Orthodox Church for the first time.